The Zomato IPO: A Bet on Big Markets and Platforms!

Zomato, an Indian online food-delivery company, was opened up to public market investors on July 14, 2021, and its market debut is being watched for clues by a number of other online ventures in India, waiting in the wings to go public. The primary attraction of the company, to investors, comes not from its current standing (modest revenues and big losses), but from its positioning to take advantage of the potential growth in the Indian food delivery market. In this post, I will value Zomato, and rather than just make a value judgment (which I will), I will also tie the value per share to macro expectations about the overall market. In short, I will argue that a bet on Zomato is as much a bet on the company’s business model, as it is a bet on Indian consumers not only acquiring more buying power and digital access, but also changing their eating behavior.

Setting the Stage

As a lead in to valuing Zomato, it makes sense to look not just at the company’s history, but also at its business model. In addition, since so much of the excitement about the stock comes from the potential for growth in the Indian food delivery market, I set the stage for that analysis by comparing the Indian market to food delivery markets in other parts of the world, as a prelude to forecasting its future path.

History and Business Model

Zomato was founded in 2008 by Deepinder Goyal and Pankaj Chaddah, as Foodiebay, in response to the difficulties that they noticed that their office mates were having in downloading menus for restaurants. Their initial response was a simple one, where they uploaded soft copies of menus of local restaurants, in Delhi, on to their website, initially for people in their office, and then to everyone in the city. As the popularity grew, they expanded their service to other large Indian cities, and in 2010, they renamed the company “Zomato”, with the tagline of “never have a bad meal”. The business model for the company is built upon intermediation, where customers can connect to restaurants on the platform, and order food, for pick up or delivery, and advertising. Along the way, the company has transitioned from an almost entirely an advertising company to one that has become increasingly focused on food delivery, and in 2021, the company derived its revenues primarily from four sources:

- Transaction Fees: The bulk of Zomato’s revenues come from the transactions on its platform, from food ordering and delivery, as the company keeps a percentage of the total order value for itself. While Zomato’s revenue slice varies across restaurants, decreasing with restaurant profile and reach, it remains about 20-25% of gross order value. It is worth noting that Swiggy, Zomato’s primary competitor in India, also takes a similar percentage of order revenues, but Amazon Food, a new entrant into the market, aims to take a smaller portion (around 10%) of restaurant revenues.

- Advertising: Restaurants that list on Zomato have to pay a fixed fee to get listed, but they can also spend more on advertising, based upon customer visits and resetting revenues, to get additional visibility.

- Subscriptions to Zomato Gold (Pro): Zomato also offers a subscription service, and subscribers to Zomato Gold (now Zomato Pro) get discounts on food and faster deliveries. The service was initiated in 2017 and it had 1.5 million plus members in 2021, delivering subscription revenues of 600 million rupees (a little less than $ 10 million, and less than 5% of overall revenues) in 2021.

- Restaurant Raw Material: In 2018, Zomato introduced HyperPure, a service directed at restaurants, offering groceries and meats that are source-checked for quality. While direct measures of revenues from HyperPure are difficult to come by, the revenues that the company shows under traded goods (which include HyperPure revenues) suggests that it accounts for about 10% of the total revenues.

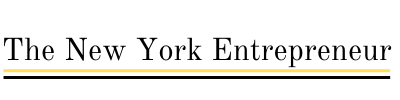

Revenues did drop in 2020, as COVID restrictions put a crimp on the restaurant business, but the quarterly data suggests that business is coming back. Along the way, the company has expanded its business outside India, with the United Arab Emirates being its biggest foreign market. That revenue growth has been driven partly by acquisitions that the company has made along the way:

|

| Source: Crunchbase |

To fund these acquisitions and other internal growth investments, the company has been reliant on venture capitalists, who have supplied it with capital in multiple rounds since 2011:

|

| Source: Crunchbase |

These capital infusions created a diverse ownership structure at the company, even prior to its going public:

|

| Source: Zomato Prospectus |

The share of the equity owned but the original founders of the company has dropped dramatically over time, as the company has had to raise capital to fund its ambitious growth agenda, and Deepinder Goyal owns only 5.55% of the company’s shares, prior to the IPO. Uber’s ownership in Zomato is a result of Zomato’s acquisition of Uber Eats India, where Uber received a share of Zomato’s equity in exchange. As revenues have grown, the business model for the company has been slower to evolve, as the company has reported extensive losses along the way, as you will see in the next section.

The Market

Zomato’s business model is neither innovative, nor groundbreaking, resembling other online food delivery companies in other parts of the world, like DoorDash, which had its initial public offering in 2020. The allure to investors comes from Zomato’s core market in India, and the potential for growth in that market. To get a measure of this potential, I start by comparing the size of food delivery markets in India to the food delivery markets in China, the United States and the EU.

|

| Zomato Prospectus and Other Sources for EU data |

The Indian food delivery market is small, relative to markets elsewhere in the world, and especially compared to China, the only other market of equivalent size in terms of population. There are three reasons for the smaller food delivery market in India, and they are highlighted in the table above:

- Lower per-capita income: Eating out and prosperity don’t always go hand in hand, but you are more likely to eat out, as your discretionary income rises. Thus, it should come as no surprise that the number of restaurants increases with per capita GDP, and that one reason for the paucity of restaurants(and food delivery) in India is its low GDP, less than a fifth of per capital GDP in China and a fraction of per capital GDP in the US & EU.

- Less digital reach: To use online restaurant services, you first need to be online, and digital reach in India, in spite of advances in recent years, lags digital reach in China, and is about half the reach in the US and the EU.

- Eating habits: Looking across the regions, it seems clear that there is a third factor at play, a pre-disposition on the part of the populace, to eat out. Looking at the number of restaurants in China and the size of its food delivery market, it is quite clear that Chinese consumers are far more willing to eat out (either in person at or with delivery from restaurants) than people living in the US and EU, especially if you control for per capita income differences.

|

| Used 2019 food delivery market number for India, and 2020 numbers for every thing else, in scaling up; COVID effect on 2020 Indian food delivery market very different from the rest of the world |

Zomato: Story and Valuation

With the lead in on Zomato’s history and business model, I can start constructing a story and valuation for the company, with the recognition that the biggest part of the story is in its macro elements. It stands to reason that disagreements about the story will be largely on those macro components, rather than in the company-specific components.

The Prospectus

To get the assessment of the company started, I began by looking at Zomato’s prospectus and all of the concerns I noted about excessive and distracting disclosure that I laid out in last week’s post on the topic, came rushing back to me. The Zomato IPO clocks in at 420 pages, much of it designed to bore readers into submission. Let’s start with the useless or close to useless parts:

- Definitions and abbreviations: The prospectus starts, and I wonder whether this is by design, with 17 pages of abbreviations of terms, some of which are obvious and need no definition (board of directors, shareholders), some of which are meaningless even when expanded (19 classes of preferred shares, all of which will be replaced with common shares after the IPO) and some of which are just corporate names.

- Risk Profile: If you did not believe my assertions about the pointlessness of risk sections in IPOs, please do read all 30 pages of Zomato’s risk profile (pages 39-68 of the prospectus). The company lists 69 different risks investors may face from investing in the company, and after you have read them all, I dare you to list three on that list that you would remember. The risk profile starts with a statement that the company has a history of net losses and anticipates increased expenses in the future and goes on to add invaluable nuggets such as the “COVID-19 pandemic, or a similar public health hazard, has had an impact on the our business”.

- Subsidiary/Holdings Mess: I find it mind boggling that a company that is only thirteen years old has managed to accumulate as many subsidiaries, both in India and overseas, as Zomato has done. Since Zomato owns 100% of most of these subsidiaries, there may be legal or tax reasons for this structure, but there is no denying that it adds complexity (and pages) to the prospectus, with no real information benefits.

- Growth & Profitability trends: The company provides three years of financial statements in the prospectus (2018-19, 2019-20 and 2020-21) and you can get a sense of the company’s growth and profitability trends by looking at the annual numbers:

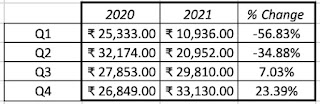

Zomato Prospectus Since the numbers for 2020 are distorted by the COVID shutdown, the company provides quarterly numbers for the most recent quarters to argue that the growth reversal in 2020 will be quickly put in the rearview mirror:

Zomato prospectus, with 2020 Q1 & Q2 numbers estimated Note the sharp and predictable drops in gross orders in the first two quarters of the 2021 fiscal year, but also the increase in gross orders in the last quarter of FY 2021 (the first quarter of the 2021 calendar year), as the shut downs ease up.

-

Unit Economics: The company does provide a sprinkling of unit economics to suggest that the underlying business is moving towards profitability. The lead in their argument is the contribution margin, i.e., the slice of the a typical order that is left as profits, after covering the costs of catering to that order:

Zomato Prospectus While the graph shows improvement, it is worth noting that the improvement is based upon a single year’s (2021) numbers. There are, however, other facts about the unit economics that lend to optimism on the story. In particular, there is some evidence in the cohort table, where Zomato customers are broken down by how long they have been using the platform, that usage increases for more long-standing customers:

Zomato Prospectus The users who joined the Zomato platform in 2017 were not only ordering three times more than they were initially by the time they had been on the platform four years, but were also more likely to continue ordering at those levels in the 2021 fiscal year, when COVID put a dent in the Indian food delivery business. This is good news, but to make full sense of it, it would have been informative to see what percent of each year’s users stayed active on the platform in subsequent years, but I could not find that statistic in the prospectus. -

Competitive Advantages: The competitive advantage section could have been cut and pasted from a dozen Silicon Valley companies in the last decade, with the networking benefit captured in a loop, where the more a platform gets used, the more benefits it provides to those on it, thus creating more usage:

Zomato Prospectus and Uber Prospectus Note the similarities between the picture to the left, from the Zomato prospectus, and the picture to the right is from the Uber prospectus, from 2019. That said, there is an element of truth in these pictures about how growth can lead to more growth, but neither picture addresses the fundamental business question of how to monetize this growth, since neither ride sharing nor food delivery has figured out how to be profitable.

- Proceeds: The company’s plans for what it intends to do with the proceeds are mixed. A portion of the initial offering will represent the cashing out of Info Edge, one of the first venture capital providers to Zomato, and that has no direct effect on the valuation. Another portion, amounting to approximately 9 billion INR will remain in the firm, to cover future cash needs.

The Story & Valuation

The story that I will tell for Zomato has several moving parts to it, but it can be broken down into the following components:

- Total Market: This is the assumption that will make or break Zomato as a company, since so much of the potential in the company is dependent on how the food delivery/restaurant market in India evolves over the next decade. As I noted in an earlier section, even allowing for robust growth in India and improved digital access, I find it hard to see the total market exceeding $40 billion, with US $25 billion, in ten years, being a more likely outcome. (In rupee terms, this will translate into a market that is roughly 1800-2000 billion INR.)

- Market Share: The Indian food delivery market is dominated by two big players, Zomato and Swiggy, with a third player, Amazon Foods, that is unlikely to fade away. In my story, I will assume that the market will continue to be dominated by two or three large players, albeit with lots of localized and niche competitors who will continue to command a significant slice of the market. Expecting any company to have a market share that exceeds 40% of this market is a reach, and I will assume that Zomato will be one of the winners/survivors. In making this judgment, it is worth noting that the online food delivery markets in other parts of the world (US, China) seem to be also approaching a steady state of a few large players.

- Revenue Share: While the market share and total market yield the gross order value for Zomato, the company posts only its share of these orders, as revenues. That number was 23.13% in FY 2020, but dropped to 21.03% in FY 2021, as shut downs put a crimp on business. I will assume a partial bounce back to 22% of GOV, starting in 2022, but the presence of Amazon Food will prevent a return to higher values in the future.

- Profitability: The profitability of intermediary businesses (ride sharing, apartment renting, food delivery) that use platforms to connect users to service or product providers is still being worked out, but the contours of how this will play out are visible. The biggest expenses at these companies are often on customer acquisition and marketing, and as growth scales down, these expenses should decrease, as a percent of revenues, delivering a profitability bonus. The biggest challenge that these businesses face are in the absence of stickiness and exclusivity, since users can have multiple food delivery apps on their devices and pick the cheapest one, and in balancing the competing needs of users and service/product providers with very different needs. For a food delivery service, restaurants and customers are integral to the business, and providing a better deal for one may come at the expense of the other. Online food delivery businesses around the world, and Zomato is no exception, are facing backlash from restaurants and delivery personnel, who believe that they are getting the short end of the stick, as the company seeks to offer lower prices and better delivery deals from customers. I will assume that pre-tax operating margins will trend towards 30%, largely because I believe that the market will be dominated by a few big players, but with the very real possibility that one rogue player that is unwilling to play the game can upend profitability. The scariest part of the food delivery market for Zomato is the identity of its new entrant (Amazon Food), since Amazon is the most fearsome competitor on the planet, willing to out-wait any company, if its intent is to capture a market.

- Reinvestment: One of the advantages of being an intermediary business is that you can grow with relatively little capital investment, defined in conventional form (as plant, equipment or manufacturing facilities). That said, reinvestment takes a different form for companies like Zomato, with investments in technology and in acquisitions, driving future growth. I highlighted the acquisitions that Zomato has made over its lifetime, with UberEats India as its most recent and most expensive illustration, but also noted that the company has burned through billions in cash to get to where it is today. I will assume that this need will continue in the near future, with a lightening up in later years, as growth declines.

- Risk: In terms of operating risk, the company, in spite of its global ambitions, is still primarily an Indian company, dependent on Indian macroeconomic growth to succeed, and my rupee cost of capital will incorporate the country risk. Zomato is a money losing company, but it is not a start-up, facing imminent failure. On the plus side, its size and access to capital, as well as its post-IPO augmented cash balance, push down the risk of failure. On the minus side, this is a company that is still burning through cash and will need access to capital in future years to continue to survive. Overall, I will attach a likelihood of failure of 10%, reflecting this balance.

With the story in place, and the inputs that come out of it, the valuation, in a sense, does itself, and you can see the summary of the numbers below:

|

| Download spreadsheet |

With my upbeat story of growth and profitability, the value that I derive for equity is close to 394 billion INR (about $5.25 billion), translating into a value per share of 41 INR. That may seem like a lot to pay for a money-losing company with less than 20 billion INR in revenues in the most recent year, but promise and potential have value, especially when you have a leader in a market of immense size. That said, the stock’s pricing (72-75 INR, per share) makes it too expensive, notwithstanding my story.

Facing up to Uncertainty

If you who are wondering whether the assumptions that underlie my Zomato valuation could be wrong, let me set your mind at rest by assuring you that they most certainly are, and it does not bother me in the least. The reason that they are wrong is simple. I do not control the future, and no matter how many tools and current information I bring to the process, there will be surprises down the road. The reason it does not bother me is because, as I have said many times before, you don’t have to be right to make money, just less wrong than everyone else. I do think there is a benefit to being open about uncertainty and facing up to it, rather than viewing it as something to be avoided or acting as if it is not there. I will use one of my favorite tools, a Monte Carlo simulation, and quantify the uncertainty I foresee in three of my most critical assumptions.

- Total Market Size: A major driver of Zomato’s value is the expected evolution of the Indian food delivery market. While I projected the market to increase to about $25 billion in my base case, that is based upon assumptions about economic growth and digital reach in India that could be wrong. In the simulation, I allow for a market size of between $10 billion (about 750-800 billion rupees) to $40 billion (3000-3200 billion INR).

- Market Share: In the base case, I assume that Zomato’s share of the market will stabilize around 40% by year 5, premised on the belief that this will be a market with two or three big players, a a multitude of niche businesses. Given the regional diversity of the Indian market, it is possible that there may be more players in the market, in steady state, resulting in a lower market share (as low as 20%) or that the niche players will get pushed out, because of economies of scale, yielding a higher market share (up to 50%).

- Operating Margin: The operating margin of 30% that I predicted in my base case for Zomato is built on the presumption that the status quo will prevail, and that the delivery companies will be able to continue to see economies of scale, while holding their slice of the order value stable. If one of the players decides to aggressively go for higher market share (by offering discounts or bidding more for delivery personnel), operating margins will tend lower (15% is my low end). If, on the other hand, Zomato is able to keep its advertising business intact as it moves forward, it could delivery higher margin (45% is my upper end).

Add ons and Distractions

The most dangerous moments, when valuing a company, are after you think you are done, as those who disagree with your valuation (on either side) come up with reasons for adding premiums for positives about the company that you may have missed, if they want a higher value, or discounts for negatives about the company that you should have incorporated, if they want a lower value. In this section, I will start with the argument that a platform with millions of users offers optionality, a reasonable basis for a premium, but one where it can be difficult to attach a number to the value. Second, I will consider whether the fact that India is a big market makes Zomato deserving of a premium, and make a case that it is not. Third, I will confront the oft used contention that value is in the eye of the beholder, i.e., that Zomato is worth a lot because other investors believe it to be worth a lot, and examine a pricing rationale for Zomato. Finally, dismissing Zomato as an investment, just because it does not make money now, or fails to meet some conventional value tests on pricing (PE, Price to Book), is investing malpractice.

1. Platform Optionality

As a company with millions of users on its platform, there is an added layer to value for Zomato or any other platform-based company, that goes beyond the intrinsic valuation above. In effect, if Zomato can deliver other products and services to the users of the platform, it can augment its earnings and value. This is the “optionality” that some investors highlight in companies with large user bases (Amazon Prime, Uber, Netflix), but while I see the basis for the argument, I would offer some caveats.

- First, not all platforms are created equal, in terms of being adding value, with platforms with more intense users and proprietary data having more value than platforms where users are transitory and there is little exclusive data being collected. One reason that I bought Facebook shares in 2018, after the Cambridge Analytica scandal, was my belief that its platform has immense value because of its reach (more than 2 billion users in its ecosystem), their engagement (Facebook users stay in the ecosystem for long periods) and the data that Facebook collects, through their engagement (posts, comments etc.).

- Second, even if you believe that there is optionality, attach a numerical value to that option is one of the most difficult tasks in investment. While there are option pricing models that can be adapted to do the valuation, getting the inputs for these models, especially before the optionality takes form, is difficult to do. With Facebook, in 2018, I arrived at an intrinsic value that was only modestly higher than the price (<10%), but used the optionality as the argument for pulling the buy trigger.

2. A Big Market Premium?

Indian and Chinese companies, especially in young and nascent businesses, have an advantage that they often play to, which is immense local markets. It is not surprising that companies play up this advantage, when marketing themselves to investors, with some analysts attaching premiums to value, just because of market size. I believe that this is a distraction, because that market size should already by incorporated into the intrinsic value, through growth and margin expectations. In my base case valuation of Zomato, I assume that revenues will increase almost ten-fold over the next 10 years, because the Indian market is expected to grow so strongly. In fact, the danger to investors, when faced with Indian and Chinese companies, is not that they will under value these companies, but that they will over value them, precisely because the markets are so big. In a post and companion paper, I describe this as the big market delusion, where investors do not factor in the competition that will come from existing and new players, drawn into the business by the size of the market, and the resulting drop in profitability.

3. A Pricing Rationale

When you value young companies with promise, the most common push back that you will get is that value is whatever people perceive it to be, and young companies can therefore have any value that investors will sustain. This is a distortion of the word value, but it is true that young companies are more likely to be priced than valued, and the pricing will be based upon a simple pricing metric (anything from PE to EV/Sales) and what investors perceive to be the peer group. With Zomato, for instance, there are two ways in which investors may attach a pricing to the company.

- VC Pricing: The first is to look at venture capitalists priced the company at, in their most recent funding rounds, and extrapolating from that number. In its February 2021 VC round, Zomato was priced at close to 400 billion INR ($5.4 billion) by a group of venture capitalists (including Fidelity and Tiger Global), who invested almost 50 billion INR (about $660 million) in the company.

- Comparable companies: The only direct comparable that Zomato has in India is Swiggy, which is still privately funded, At the risk of stretching the definition of “comparable firm”, I compare Zomato’s pricing (using the projected 72-75 INR share price on the IPO) to the pricing of Doordash, which went public in 2020:

One of the perils of pricing is that you can find almost always find a way to back up your preconceptions, if you try hard enough. Thus, if you are a Zomato bull, you could point to the EV/User and argue that it is cheap, relative to Doordash, whereas if you are a bear, you can point to Current revenue and GOV multiples, to make the case that Doordash is cheaper. To make the argument even messier, using forward multiples, where you scale the current enterprise value to expected revenues or earnings in 2031, make the Zomato case stronger, since it has higher expected growth than Doordash does.

The bottom line is that pricing is not a panacea for uncertainty or a cure for bias, since the uncertainty is just pushed into the background and there is plenty of room for biases to play out, in how you standardize price (which multiple you use) and and what your comparable are.

4. It is a money loser

There are good arguments to be made against investing in Zomato at is proposed offering price, but one of the emptiest, and laziest, is that it is losing money right now. I know that for some value investors, trained to believe that anything that trades at more than 10 or 15 times earnings or at well above book value, this argument suffices, but given how badly this has served them over the last two decades, they should revisit the argument. The biggest reason that Zomato is losing money is because it is a young company that is trying to take advantage of a market with immense growth potential, not because it cannot make money. In fact, if Zomato cut back on customer acquisitions and platform investments, my guess is that it could show an accounting profit, but if it did so, it would be worth a fraction of what it is today.

Conclusion

In investing and valuation, there is the presumption that rules and even the first principles of investing change as you go from one market to another, and this is particularly true when comparisons are made between developed and emerging markets. I believe that the first principles of valuation are the same in all markets, and I hope that I have stayed true to that belief in this post. I valued Zomato, using the same process that I used to value Doordash, with the country-specific effects being incorporated into my growth and risk projections. While I did take issue with some of the holes and over reach in Zomato’s disclosures, I ran into the same challenges, when I valued Doordash. Zomato is a money-losing, cash burning enterprise now, but it has immense market potential and is on track to delivering on a viable business model. It will face plenty of challenges on that path, both at the micro level (management, competition) and at the macro level (economic and political developments in India). I believe that the company is currently over priced, given its potential, but I would have no qualms about investing in the stock, if the price drops in the near future, with the full understanding that this is a joint wager on a company, a sector and a country.

YouTube Video

Data & Spreadsheets